By WLRG contributor

For many years, members of the “Wayne’s Legion Research Group” (WLRG) have been conducting archaeological projects here in west-central Ohio. The all-volunteer group mainly focuses on exploring the region’s early historical period (1750-1820) through archaeology. Published results of various WLRG projects have been featured in “Ohio Archaeologist,” “American Digger Magazine,” the book “A Gathering of Eagles,” and many newspaper articles. Also, team member Greg Shipley has traveled extensively to share his numerous PowerPoint presentations and features of WLRG activities on social media. This particular project has been a joint effort of the WLRG and the “Friends of Fort Jefferson.”

Historical background of the excavation site

The weary army under the command of Major General Arthur St. Clair arrived at what is now Fort Jefferson, Ohio, on Oct. 13, 1791. This army consisted of the 1st and 2nd American Regiments, the Kentucky Militia, and an assortment of “camp followers” (around 1,700 in total). St. Clair’s mission was to subdue the British-supported Miami tribe that was located at modern-day Fort Wayne, Indiana. General Josiah Harmar’s 1st American Regiment failed to accomplish this complicated task a year earlier.

Marching out of Fort Washington (Cincinnati, OH), St. Clair had established Fort Hamilton (Hamilton, OH) and now decided to construct what would later be named Fort Jefferson (Fort Jefferson, OH). Leaving a garrison and two cannons behind at Fort Jefferson, the army continued their march north only to be crushed a few days later at the Battle of the Wabash (modern Fort Recovery, OH) by a confederation of several Native American tribes led by Miami Chief Little Turtle. At the end of the battle, the Americans had suffered approximately 900 casualties compared to the native’s relatively few. This action was considered a monumental victory for the Indians and their British allies.

What remained of St. Clair’s force retreated back to Fort Jefferson which, for two years, would be the farthest advanced U.S.-held post in the north-western territory. In October 1793, Anthony Wayne and the Legion of the United States established “Greene Ville,” six miles north of Fort Jefferson. This huge fortification of over 55 acres became the headquarters for the U.S. troops operating in the vicinity. At this point, Fort Jefferson became a supply post until it was decommissioned in 1797.

The archaeology

“The Friends of Fort Jefferson” (FFJ) currently owns a 17-acre tract of land located south and adjacent to Fort Jefferson Park. This parcel has been the focal point of past WLRG projects conducted in 2018 and 2022, which will be covered in future articles. Working with the WLRG, the FFJ wanted to see if any evidence of St. Clair’s Oct. 13-24, 1791 encampment existed. (see Fig. 1).

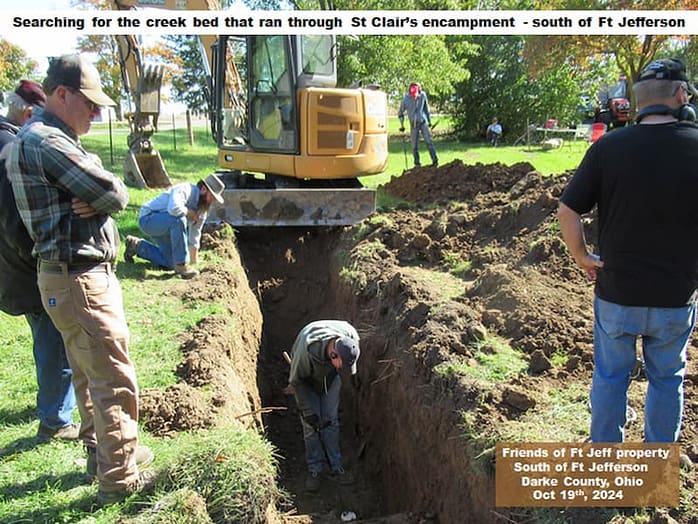

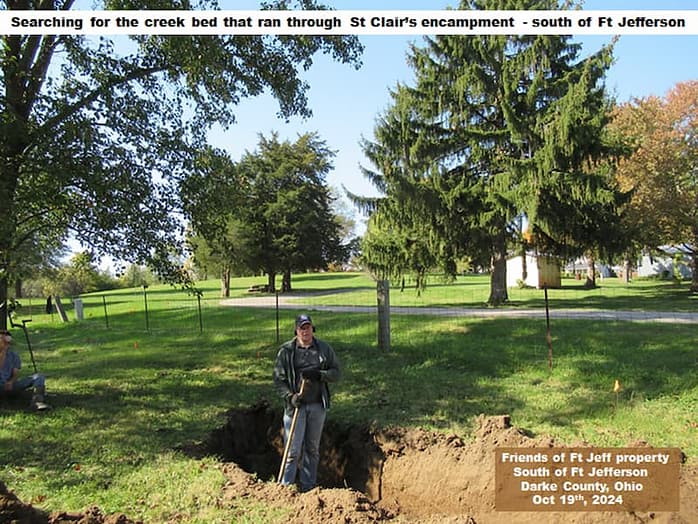

In his journal of the campaign, Winthrop Sargent states that an eight-foot-wide creek divided the camp. The creek drainage area of the camp (shown at the bottom of the map) was located immediately to the south of the north fence line of the FFJ property boundary, close to S.R. 121. Preliminary soil samples showed that the drainage averaged about eight feet wide and had several feet of fill dirt over the original creek bed. A plan was then devised to remove the dirt from a section of the creek run and hopefully discover discarded/lost artifacts from the encampment occupation.

The time of the project finally arrived on Oct.19th, 2024, with several team members ready to work. As the fill dirt was being removed from the target area, the dirt was spread out and searched with metal detection equipment. It soon became apparent that the fill material was obtained locally as there were 1790s artifacts mixed in with other relics from the 19th and 20th centuries. The filling depth abruptly ended at a sterile clay stratum at about five feet deep and was absent of the typical stone bottom normally associated with many creek drainages. As the site material was being carefully investigated, many tableware and food storage crockery sherds from the 19th and 20th centuries were discovered, but not one sherd from the 1790s was found. After a thorough investigation, the site was leveled back out and will be grass-seeded in the spring of 2025.

Conclusions and results

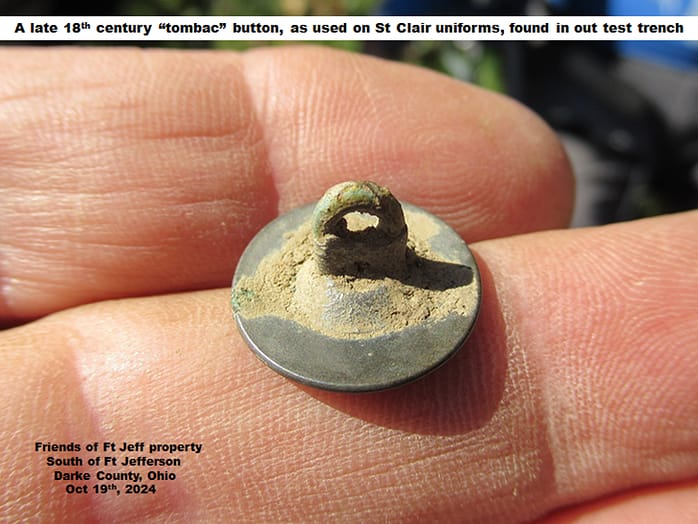

Surprisingly, the only fort-period artifacts discovered in the original creek bed/bank stratum were a couple of rifle balls and a “tombac” button (see Fig. 4).

Conversely, another surprise was the amount of 1790s artifacts discovered in the fill-dirt, which indicates that the fill material originated at or near where Fort Jefferson once stood. A major archaeological dig was held at the fort location in 1930. Could the fill dirt have originated from that excavation? We’ll never know for sure, regardless, salvaging these rare artifacts from America’s earliest days of the north-western frontier was definitely worth the effort.

The following descriptions of the pictured artifacts help identify the fort-period items that came to light during the project. Fig. 2 shows various lead ball and flintlock ammunition from left to right: 8) buckshot, 24) rifle balls, and 2) .62 cal. Charleville musket balls. The irregular shape of most of the balls indicates fired specimens.

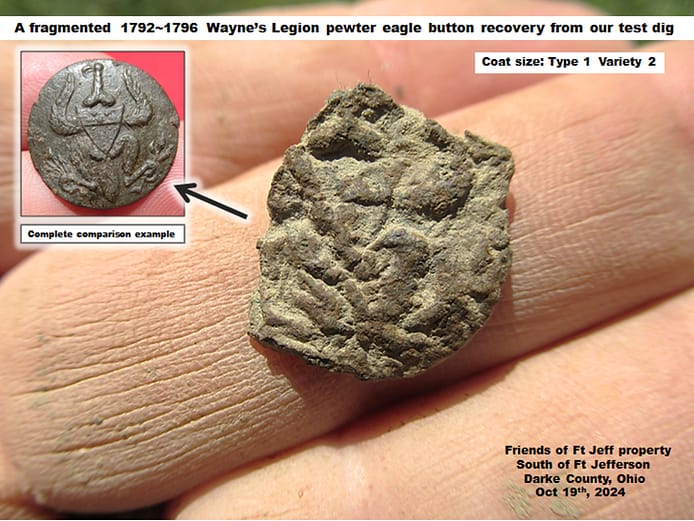

Fig. 3-1 & 3-2: Two badly corroded pewter Wayne’s Legion uniform coat buttons (1792-1796) were found in the fill. Pictured are the recovered buttons, along with examples shown for comparison that were found at Greenville, Ohio.

Fig. 4: “Tombac” buttons such as the one shown here were made of a “silvery” alloy that preserves well in the soil. These were utilized by the troops and civilians alike during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This button could have very well been lost from a 1st or 2nd American Regiment uniform that St. Clair’s troops wore. Fig. 5a: The three shoe buckle fragments shown here exhibit a green patina from 230+ years of exposure. Shoe buckles were pretty much out of style by the 1790s. Fig. 5b: Here’s a comparison photo of a complete shoe buckle example. Figures 6-9 show the excavation in progress.

The Friends of Fort Jefferson and Wayne’s Legion Research Group would like to thank the Miller family for their generous excavation work during this endeavor. We’re looking forward to more projects in the future, so stay tuned for additional articles about the groups’ activities.