[NOTE TO READERS: This is one of a series of short stories about my dad’s experiences in WW2, based on his letters, his diary, his pilot’s log book, and the many documents he saved from his time in the Navy, and other historical records. Individual conversations and scenes I have invented, though they are informed by the records in my possession.]

Weather had us grounded. Like crystal daggers, icicles hung off the wings of the yellow trainers on the flight-line. The ceiling was low and gray, a solid overcast. Pulling my watch cap lower around my ears, I shrugged deeper into my leather flight jacket and turned up the collar. Snow whipped around the aircraft, forming white, whirling eddies. It was Saturday, a scheduled day off, but I guess the snow storm put the exclamation point on it.

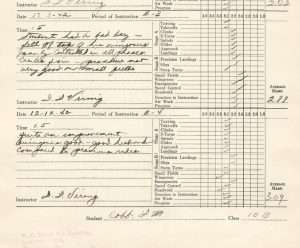

Thursday had been a bad day—a terrible day. My ears were still stinging with Virnig’s criticism. He was climbing my backside before we even took off. On my evaluation sheet he wrote, “Student had a bad day – fell off top of his wingovers; poorly controlled in all phases; circles fair – procedure not very good on small fields.”

I didn’t want a day off. I wanted to get back in that cockpit and do it right this time. Maybe Virnig was having a bad day and took it out on me. I indulged that petty thought for about sixty seconds. No, Cobb, I said to myself, you deserved it. You earned it, but you don’t have to like it.

Frustrated, I hung my head, which caused a little clump of snow to fall between my watch cap and my collar. It proceeded to make a cold, wet trail as it slid down my spine. Didn’t much like that either, but it snapped me out of my pity party. In my mind I heard dad’s voice, He’s hard on you, Lou, because he’s trying to keep you alive. One day soon you’ll be glad he taught you to fly right.

I shivered and nodded. Yeah, you’re right, Dad. I’m gonna shut-up, listen, and learn. I jammed my hands into my flight jacket pockets, turned around, and headed for the mess hall.

**********

The members of a cadet cadre move together through the different stages of primary flight training. If someone falls behind (except for illness or other extenuating circumstances) they are washed out of the program. I was determined not to be a washout. Truth be told, I wasn’t even close to washing out, but our instructors were pushing us hard to master military flying skills with consistent excellence. An average flier would not live long against the skilled Japanese pilots in their agile Zeroes. So our instructors kept up relentless pressure and threats. Every member of our cadre put his head on the pillow each night convinced he was but one screw-up from joining the ranks of the black-shoe Navy. Not that there was any dishonor to being a sailor, but we all aspired for the coveted status of naval aviators.

As my flight hours increased, so did my skill. On a bitterly cold December 20—the low temperature in St. Louis was 12 degrees, a little tough on a southern boy—I was flying an N3N-3 Yellow Bird, Bureau number 2876. That baby has an open cockpit. I don’t even want to know what the wind chill is at cruising speed. I took the ship up for a ninety minute hop, practicing the various stage B maneuvers, which were slips, steep turns, and precision landings. When I finally landed my face was so frozen I couldn’t move my lips to speak.

Steep turns are particularly difficult to master for a novice pilot. Because of the steep attitude of the aircraft, the vertical lift produced by the wings diminishes. Consequently, the aircraft tends to drop during the turn, so you have to compensate by increasing power to maintain altitude. Sounds simple, right? Trust me—it isn’t. At that stage of pilot training, you feel like the aircraft has three dozen gauges and indicators, all of which you must watch at the same time. You’re working with your feet and hands together, trying to coordinate your ailerons and rudder action so you’re banking, not skidding, through the turn. One eye is on the bank indicator to make sure you’re at the proper bank angle, the other eye is watching your compass so you pull out of the turn on the right heading. Meanwhile, your third eye is on your airspeed indicator, because you’re supposed to maintain a constant airspeed through the turn. And the fourth eye is on your altimeter—because you have to maintain your precise altitude throughout the turn.

What? You don’t have a third eye, or a fourth eye? Exactly. The only solution is to practice until the aircraft ceases to be a machine you are operating and instead becomes an organic extension of yourself, and you make all the required control adjustments instinctively. You learn to wear the airship like a glove. Or you wash out.

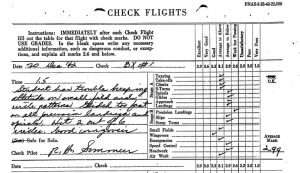

On that cold December 20, 1942, I landed and taxied to the flight line. Waiting for me there was Ensign Summers. “Step into the ready room, Cobb, long enough for your face to thaw out. Grab a cup of coffee, warm up, then you’re going up again with me as passenger. I want to evaluate your progress.”

Twenty minutes later we were back in the air. Other than telling me what maneuver to perform, Summers was silent during the entire flight. I was tempted to look back and see if he had frozen to death. He must not have, because an hour and a half into the flight he told me to put her down.

We both climbed out of the airplane, stiff with cold, and headed for the ready room. Summers got a cup of coffee, and we sat at the table. “Your wingovers were quite good today, Lou. Much better than last time. You’re still having trouble maintaining altitude in turns, and you need more work on precision landings and spirals. But you passed stage B—congratulations, I’m giving you an upcheck. Your total score today was 2.99. I think you’re better than that. I want to see that total improve.”

In the Navy’s system of grading, 2.99 was “Average to Below.” You can bet I was not satisfied with that score. The one bright spot in that freezing ninety minute flight, besides the upcheck, were my wingovers. I felt like I’d corrected my earlier problems with the maneuver and was pleased that Summers agreed.

**********

Our barracks was large enough to hold several different cadres of cadets. It had somewhat of a lounge in it, with chairs and couches and a few tables. We used it for late-night bull sessions, for talking about girls, for studying, and as a forum for our very righteous beefs (cough, cough) about the food, unfair evaluations, our instructors, the navy, and just about anything else young men might complain about.

When we arrived at Lambert at the end of October, the barracks was empty. In January, however, a new cadre moved in with us. These boys had just graduated from ground school and were just starting stage A of primary flight school. They hadn’t gone up yet, and so had not been humbled by the mystery of all those knobs, switches, levers, pedals, controls, and gauges, all of which you must operate simultaneously. But they had just completed ground school, and so they were pretty cocksure and full of themselves. I reckon our cadre must have been the same at that stage of the game.

Learning to fly has some interesting effects on your ego. Wannabe pilots just out of ground school have a lot of unearned self-confidence. They know about Bernoulli, they grasp the physics of flight, and they know that the Pacific war won’t be won without pilots (meaning them, personally). They graduate from ground school figuring that they have mastered most of what they need to know. They don’t know what they don’t know, but the old ego is flying high.

That is, until the first time their instructor puts them into a flat spin and they barf all over the cockpit. That brings ‘em down a notch or two. Then the maneuvers—even the introductory ones—will humble them a little more. Before long, the newbies are convinced they’ll never learn to control the airplane properly.

I should say, however, that there is a wide gulf between what a civilian learns in civilian pilot training, and what is required in military training. It’s one thing to fly a steep bank when no one else is nearby, it’s a completely different matter when you’re doing it at cruise speed in tight formation with three other aircraft. Fatal training accidents are not uncommon.

Back to the ego: at some point in intermediate flight training, as their skill improves, the confidence returns. By the end of intermediate they feel like masters of the universe. Until they hit carrier qualification, when they learn to fly terrified—but that’s for another tale. In any case, when the training is complete and you’ve got multiple combat sorties under your belt—well, then, you are a master of the universe.

It was late one evening in January ‘43, just before lights out, and the brand new cadre was sitting in the lounge with us. I mentioned to my cadre that I was flying a different aircraft. “Hey, guys, last few hops they’ve had me in an N2S-3, a Stearman Kaydet. Is anyone else in our group flying Stearmans?”

Several others raised their hands, then some know-it-all from the new cadre piped up. “They’re all Stearmans, so what? Big deal.”

My buddy, John Carpenter, turned to the new guy. “Hey, Sprout, children are not to speak unless spoken to. Besides which, you’re wrong about that. The N3N is a different aircraft from the Stearman. Similar, yes, but not identical.”

“Hey, gramps,” the young buck replied to Carpenter, who might have been all of two years older, “you might want to confine your comments to things that you actually know about. The N3N is a Stearman.”

Now that was a particularly offensive statement to us old pros. As required, my cadre had memorized all the physical airframe characteristics of the N3N-3 biplane, as well as its flight parameters. For example, we knew it stalled at forty-four knots and cruised at seventy-seven knots. Maximum speed was one hundred nine knots, service ceiling was fifteen angels. These were not just numbers—they were important data points for pilots to master, for flight efficiency, for safety, and eventually, for combat.

John was a pretty aggressive guy. I wondered how he’d respond to the idiot. Would he take the newbie apart, physically, or just put him in his place verbally. I noticed several of us tensed, ready to restrain Carpenter if need be. He was one of the best pilots in our cadre, and we didn’t want to see him get into trouble.

Thankfully, John chose the verbal route. “No, the N3N is not a Stearman. Just because they’re both painted yellow doesn’t mean they’re the same, Dilbert. And for your information, genius, I actually do know about Stearmans. My pop builds ‘em.”

“Prove it, then. How are they different?”

“For starters, the airframe is constructed differently. The N3N has a riveted fuselage, the Kaydet Stearman is welded steel tube. The flight characteristics are a little different, too. The Stearman’s ceiling is 2000 feet lower. The N3N has a slight power advantage on the Stearman’s powerplant. The Stearman is a shade lighter. Those are just a few of the differences, not counting the fact that Boeing builds the Kaydet, and the Naval Aircraft factory builds the N3N.”

The chastened smart-aleck turned red at being humbled in front of his cadre. After a moment he asked, “Does the Kaydet handle differently than the N3N?” The question was obviously a peace offering, but the interchange clearly established the pecking order between our two groups.

I shook my head. “No, not appreciably, not unless your maneuver is pressing the envelope. But they’re both a beast to handle in a crosswind landing. They both tend to ground loop.”

Terry Johnson added, “You want a week’s worth of bad evals? Just ground loop when your instructor is aboard. Take it from me—I did it twice. My ears are still burning from his, ah, very creative use of the language. I heard words I never knew existed in French or English, but believe me—I didn’t ask for definitions.” Johnson was the lone member of our cadre from Canada. He was here both as an observer and participant in the Navy’s training program. I assumed he would take what he learned back to the Royal Canadian Air Force pilot training program.

Once we had established who was the bull of the herd, we stopped getting into spittin’ contests with the new cadre and buckled down to help them pass their training stages. They turned out to be a pretty swell bunch of guys.

**********

“Sir, you wanted to see me?”

It was the morning of January 27, 1943. I had no idea why Virnig sent for me. By now my flying skills had much improved, so I wasn’t concerned that I was washing out. My recent evaluations had actually been good. I stood at attention in his tiny office. Wardlow, one of my other instructors, was leaning against the wall, studying me.

“At ease, Lou. In the last two weeks you’ve proved to both of us what you are capable of. You’ve done well. You’re ready to move on, so it’s time to choose your specialized training. What’s your preference?”

The training programs diverged at this point in their specialties. While our preferences weren’t guaranteed, we were given the opportunity to choose specialized training. Those who marked VO-VCS went on to become flying scouts for battleships and cruisers. VP was a designation for a patrol squadron, VF for fighters. Additionally we could ask for carrier operations, or a position as a future instructor.

It didn’t take me a second to choose. “Fighters, sir.”

The two men looked at each other and grinned. Virnig looked back at me. “Okay, what about your second choice?”

I thought for a moment. “Well, sir, I’ve done well in navigation, so I guess that would be patrol. But whether it’s fighters or patrol, I want to be carrier based.”

“That’s what we hoped you would say, Cobb.” He shoved a specialized flight training request form across the desk. “Mark your preferences, sign it, and then I’ll send it upstairs. The squadron commander, the medical officer, and ground school officer in charge will add their two cents, and then it goes to the Selection Board for approval. With your scores, it’s pretty much a formality. The Navy is building a lot of flattops and needs several boatloads of carrier-qualified pilots.”

Virnig stood and shook my hand. “You’re done here. Get your gear together, you’re headed for Pensacola. It’s a little warmer down there than up here. Good job and good luck, Lou.”