ON PATROL | APRIL 19, 1944

After scanning my instruments, I studied the sky in front, side to side, above and below, and finally behind. Failing to maintain this vigilance was liable to get me shot down. While the quality of the Japanese pilots had declined somewhat since ‘42 and ‘43, and the Zero couldn’t take the punishment my F6F could, carelessly disrespecting the enemy’s capabilities could end my career and probably my life in a flaming, downward spiral.

I scanned my instruments and the airspace around me again. My engine temperature was on the high side of the normal range, so I made a small adjustment to the fuel mixture and manifold pressure. Once the aircraft was all trimmed out to cruise at 20,000, I found that I had to force myself to concentrate. I couldn’t get the early morning’s tragedy out of my mind. We lost three good men during the predawn strike launch. Shortly after takeoff, one of the TBFs clipped the superstructure of a cruiser off the carrier’s starboard bow and went down in flames. Neither the pilot nor crew was recovered. Lieutenant Jones speculated that, in the darkness, the pilot had mistaken the cruiser’s running lights for that of a squadron mate and was following him, intending to form up. Losing a man to enemy action was bad enough, but losing three to an innocent mistake was a tragic waste.

I shook my head to clear it. Can’t think about it now. Focus, Cobb, or you’re liable to join them in Davy Jones’ locker. I scanned my instruments and the sky around me. Satisfied, I noticed that the engine temp was back down in the middle of its optimal range.

My headset crackled, “BLUE FLIGHT, this is BLUE-1. Stay sharp. If that snooper is still here, we should see him before long.”

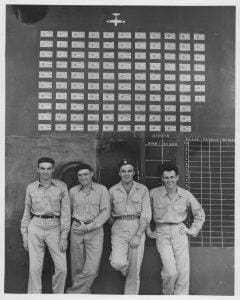

I grinned to myself. Gill always began a mission with strict, by-the-book radio etiquette. But after the first thirty minutes or so—or perhaps it was once we were out of sight of the carrier, I don’t know—he would simply go informal, using last names and sometimes even first names. That’s one thing I really appreciated about Lieutenant Gill: he was straight-laced and buttoned-down when the situation required it, but otherwise he was just down-home.

I felt the same about Lieutenant Jones, who was in overall command of VF-5. He inherited the squadron back in March when our old skipper got called back to the States. I wasn’t sure about Jones when he first took over the squadron, but he turned out to be a swell guy and a great pilot.

I scanned everything again. Instruments normal, no sign of the snooper. Looking for that Jap scout plane reminded me of an argument I had when the Yorktown was anchored at Majuro in the Marshall Islands about ten days ago.

Mac had copped a jeep from the motor pool, so he and I were touring the island, exploring the buildings and defensive emplacements the Japanese had constructed when the island was theirs. We ran into a black-shoe lieutenant named Ray Wilson. Wilson was assigned to the USS New Jersey, one of the Task Force 58 Iowa-class battleships. He seemed like a pretty good guy, so we invited him to tour with us. We got to talking about TF-58’s next target—Hollandia. It was supposed to be a secret, but the rumors of the upcoming operation were everywhere.

“It’s a good thing Mitscher is sending battleships to protect your carrier when we hit Hollandia. You’d be pretty helpless without us as an escort,” he said confidently.

“That’s the dumbest thing I’ve heard in a long time. You’re nuts, Ray,” I said. “What are you talking about?”

“Really, Lou, think about it: the Yorktown’s biggest gun is, what, a five incher? That’s a popgun compared to the armament on my ship. The New Jersey can throw a sixteen-inch shell twenty-five miles. And scuttlebut says the Japs are mounting eighteen-inchers on their big battleships. Your carrier would not last five minutes in a surface engagement.”

McClelland laughed. “Hey, Ray, haven’t you ever heard of Pearl Harbor?”

“Of course, flyboy. What’s that got to do with anything?”

“Carrier-based aircraft made mincemeat of the battleships.”

“That’s just because it was a dirty sneak attack.”

“No, it’s because a carrier can hit your battleship from three hundred miles away, long before the carrier is in range of your sixteen inchers.”

I grinned at Wilson. “He’s right, Ray. How many battleships engaged at Midway? None of them ever came close to firing a shot at another ship. They were too busy fending off aircraft. And who scored at Midway? It was the carriers. Your big boat is good for shore bombardment and for providing an anti-aircraft screen. But other than that, the day of the battleship is over. We’ll hit you before you even know where we are.”

He didn’t like hearing that, but it’s true. The brass ring of naval warfare has transformed into a contest to find and sink the enemy’s carriers before he finds ours. That’s why we had to find that snooper before he found the Yorktown.

Skipper banked left in a standard two-minute turn, and I goosed the throttle a bit to stay on his wing. We’d reached the edge of our patrol sector, and he was turning back into it for another pass. I looked over and saw Boze and Mac expertly maintaining station on the other side of Gill, keeping a tight formation. It made me proud to be part of this group of skilled, professional pilots.

Making another scan of my instruments and airspace, I observed scattered clouds below, down around ten thousand feet. The view from up here was really swell—a broad expanse of blue, punctuated by a few cotton-ball clouds scattered across it. As the afternoon was drawing on, the sea to my west glittered with reflected sunlight. Beautiful.

Suddenly I caught something out of the corner of my eye. I focused in that direction, but could not detect what attracted my attention. I scanned my instruments again and all around me. Then I looked back toward where I thought I’d seen something. There it was! By chance I was looking in the right direction when a dark dot appeared against the white of one of the scattered clouds, traversing it. I would have never picked it out if it had not been against the whiteness of the cloud. Against the backdrop of the dark sea, the aircraft was almost invisible.

I keyed my mask microphone. “Tallyho! This is BLUE-3. Two o’clock down, maybe four miles, one Betty, angels fifteen.”

After a moment, Gill responded. “BLUE-3, this is BLUE-1. Negative, negative, I don’t see anything, Lou.”

“He was silhouetted against a cloud, sir. Look! There he is again!”

“Ah, roger that, now I got him. BLUE Flight, this is BLUE-1, acknowledging one Betty.

“Boze, Lou and I are engaging him. You and Mac keep your eyes open. He could be a decoy. Might be a second one down on the deck that we’re not supposed to see. I reckon he might even have fighter cover, so stay sharp.”

I reviewed what I knew about the Mitsubishi G4M as we prepared to jump him. The Betty was the Imperial Japanese Navy’s long range bomber. Fast and capable, it had a long range, high ceiling, and could carry a lot of ordnance. It was an excellent land-based scout plane. It was prickly, too, with deadly armament in the nose, tail, waist, and top, a mix of 20mm cannon and 7.7mm machine guns. But it couldn’t take much punishment. One hit could turn the thing into a flaming funeral pyre, a characteristic that resulted in American fliers nicknaming it the Zippo, after the venerable lighter.

Gill maneuvered until he could attack out of the sun, and I stayed with him until he rolled over into his dive. I orbited in a tight circle, ready to back him up if he was jumped by any fighters we had not seen. The Jap didn’t realize he was under attack until skipper started firing—then the Betty began jinking and dove for the deck.

Once skipper was clear I started my attack, only by now the Jap was ready and waiting for me. I could see the winking muzzle flashes coming from his tail and dorsal cannons and machine guns as he brought his weaponry to bear. The tracer rounds looked like bright fireflies, floating up toward me with deceptive slowness. As they drew nearer they seemed to gain incredible speed, flashing past in a deadly streak of light. I could sense some of his rounds striking home. To this day I’m not sure if I actually heard them hit, or maybe I imagined it as I felt the impacts on my Hellcat, but it sounded like pouring a handful of gravel into an empty metal bucket.

I sent my own fireflies back, triggering my starboard fifty cals. I was working a low angle deflection shot, leading him the way I used to lead ducks on the wing back home. As I roared past the bomber I saw that I’d scored a lucky hit on the dorsal cannon. The gunner was limp, face down, probably held in place by his shoulder harness.

Flying under the bomber, I banked to the left and did several fast rolls to throw off his waist gunner’s aim as I put some distance between us before climbing for a second pass. I pulled into a climbing turn and saw Lieutenant Gill pop out of a cloud beneath the diving Betty. He rolled right behind the bomber and leveled out, triggering his guns. He was scoring hits on the bomber’s starboard wing. Even from where I was, I could see he was chewing off pieces of it. The Betty began trailing smoke momentarily, and then the whole aircraft caught fire. Skipper followed it down, recording the kill on his gun camera.

We rejoined Boze and Mac at twenty thousand feet. For the next several hours our patrol was uneventful as we crisscrossed the sector. Nothing but clouds and the deep blue sea. Toward the end of our patrol period a layer of stratus clouds developed just above us.

Gill keyed his mic, “Boze, you and Mac climb up to thirty angels. See if you can get above the layer. I want to make sure nothing is sneaking past us, shielded by those clouds.”

“Aye, aye, Skipper. Climbing to thirty.”

In a few minutes Lieutenant Bozard radioed that the layer only went up to twenty eight, and that the sky was just as empty up there as it was down below. Thirty minutes later it was time to return to the ship, and the four of us formed up together.

“Lou, are you picking up the YE radial? That Jap must have clobbered my antenna, because I got nothing.”

“Skipper, I’ve got the Yorktown’s YE at one-zero-five degrees.”

“Roger that. One-zero-five. Thanks.”

A few minutes later I noticed Lieutenant Gill staring at my Hellcat. He motioned for me to stay put and then fell back a bit, circling under me. “BLUE-3, you’ve got a little road rash. I can see some damage to your tail. You must have caught a little lead from that Betty. How do your controls feel?”

I waggled my wings and used the rudder to slew it back and forth, checking the yaw, pitch, and roll. It felt fine. “Pretty normal, sir. The aircraft seems responsive.”

“Okay, good. That Betty must not have hit anything important.”

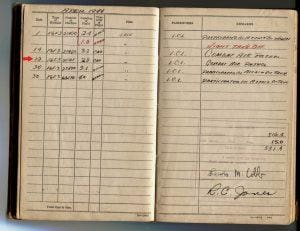

[Editor’s Note: Stay tuned for part 3! This account has been constructed primarily from Lou Cobb’s WW2 diaries. After part 3 is posted, Cobb will post an epilogue indicating what parts of the story are factual history, and which parts were necessary creations for the sake of the tale.]