Lewis M. Cobb is my father, Helen is my mom. They were married in July of 45, after dad returned home from his tour on the Belleau Wood (CVL-24), with Fighting 30 (VF-30). Dad retired in 1966 as a commander in the regular navy, having survived many, many carrier landings (the planes normally survived his landings, as well!). He served in combat in WW2, Korea, and Vietnam, on several different carriers, earning 3 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 11 Air Medals, and numerous other lesser citations. He passed away in 2011 after serving his country and his church with honor.

So, what was fiction, what was fact? The principal activity in the Hollandia Strike story is historical. On April 19, 1944, the carriers of Task Force 58 were softening up the defenses of Hollandia in preparation for landing the marines.

All the data pertaining to aircraft (American and Japanese) are factual, including the positions of switches and controls. All the names in the entire story with the exception of Ray Wilson (whom I invented) are factual, including their positions and ranks in VF-5 on April 19, 1944. All of the dialog in the story is a product of my imagination but is based on research. I hope it is not too far off from how these pilots would have communicated at the time. My apologies to actual pilots in case I managed to scramble some of the details. I’ll welcome your corrections.

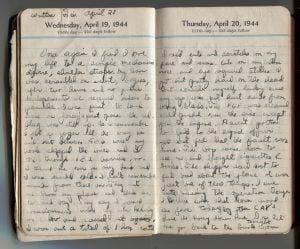

My dad’s use of the word “swell” is quite accurate—it appears in his diary many times!

In Part 1:

The visit to the Udvar-Hazy Center with my brother, L. M. Cobb, Jr., was real, complete with the Yorktown Hellcat hanging from the ceiling, The flashback was not real. I invented it as a means of launching us into dad’s world on April 19, 1944.

The Combat Air Patrol (CAP) in which my dad was launched is factual, and the flyers named were actually flying with him, as near as I can tell from records. Several inbound bogies had been detected on. All the information on deck and launching operations is factual, to the best of my ability to research it.

In Part 2:

The early-morning loss of the TBF by collision with a cruiser actually happened, but according to dads diary it happened on 4/22/44. I conflated it into the tale.

Dad’s initial concerns about Lieutenant Jones, followed by his tremendous respect for the man, are true, and are taken from various entries in dad’s diary. The entire story about Ray Watson is a fabrication, intended to make the historical point that naval doctrine was slow to shift from large surface engagements dominated by battleships, to a carrier-based air war. This constituted a major shift in both naval budget and priority in the United States during WW2. I added this piece also to help the reader get the sense of urgency regarding finding the snooper before it found the carrier, which in fact would be a huge concern at the time.

The detection and shootdown of the Betty (two of them, actually) did occur on 4/19, but was accomplished by a different CAP, not dad’s. My tale of dad’s engagement with the Betty on his CAP was pure fiction. However, it is true that dad’s CAP was launched because of radar-detected bogies, but dad’s flight was unable to locate them. Consequently, there was no damage on dad’s plane when he landed on the carrier.

In Part 3:

As can be seen in the photograph of the upside-down Hellcat, dad did not jettison his drop tank—probably because everyone was anticipating a normal landing.

The story of dad creaming a Hellcat a week before is factual (it occurred on 4/14/44), and I might turn it into another short story. The description of the weather during that event was factual, coming from his diary.

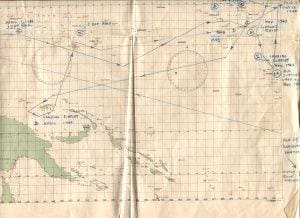

It is very likely that there were several photo-recon TBFs launched on 4/19/44. I have an original copy of the Yorktown’s Air Group Plan of the Day for 4/21/44, showing such launches. Whether the TBFs actually interfered with the landing of dad’s CAP, I do not know. The photo-recon guys did have both landing and launch priority, however, as the Task Force needed reliable info to plan the next strike. Whether or not the carrier would have communicated to BLUE FLIGHT the way it did I don’t know. They very likely would have been using an early form of IFF (Identification Friend or Foe).

The various descriptions of operations in the Task Group (ditching, recovery of pilots, Bosun Chair, etc.) are pretty accurate, based on my research and discussions with dad before he died in 2011.

And that brings us to The Crash. First—it actually happened. The photos are authentic. The Bureau Number of the upside-down Hellcat is stamped on the backside of the large official Navy photo. It matches the Bureau Number in Dad’s pilot log for the 4/19/44 CAP. How or why the crash happened—I don’t know. My description of the crash is what I envisioned might happen on a hard, tail-first landing if the hook did not catch.

Dad says his hook skipped the #5 and #6 wires, and the Hellcat tore through the first two barriers. He sustained several injuries (eyes, nose) and was removed from the plane unconscious. As a result he was taken out of the flight rotation during his recovery. The aircraft was pushed over the side.

Dad’s eye patch was removed on 4/27, but the doctor would not let him fly because he couldn’t pass the eye exercises. On the 28th, he wrote that the Doc said he was not grounded, but he’d rather dad didn’t fly yet—still concerned about his eye. However, there’s a gleeful entry in the diary on 4/30: “I fooled them and flew today. I was on standby on the 1st hop in the A.M. and they launched me by mistake! We were escort. We strafed the strip on Eton and a small island covered with installations.”

A big thanks to my brother Lou for encouraging me to write the tale and for helping me sift through the records that dad kept. Lou and I typed up dad’s diaries from his ‘44 tour on the Yorktown, and his ‘45 tour on the Belleau Wood. It was an honor and a privilege.