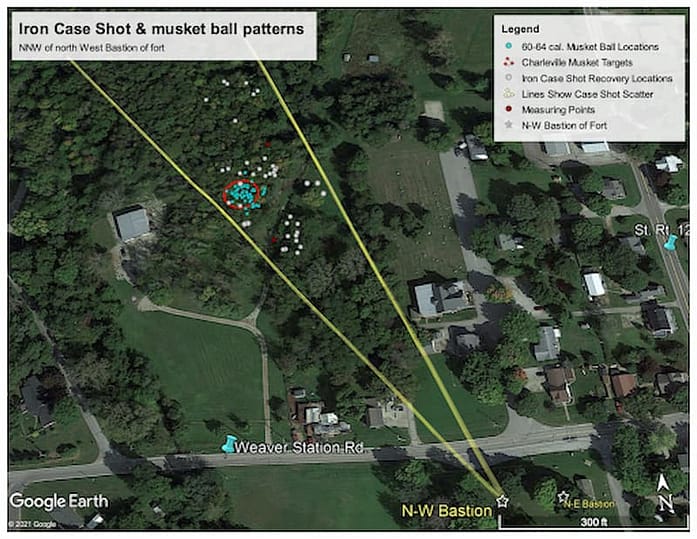

White dots are locations where the Iron Case Shots were recovered.

The blue dots in the red circle are 62 cal. musket balls found in the target practice area from the Part 1 article.

What is an iron case shot, and how does it fit into this article? Case shots are many shots that are put into a cylindrical tin canister that fits the bore of the particular size of the cannon from which it is fired.8 The weight of the shot, tin cylinder, and wooden bottom must be the same as the solid shot fired from the particular size of the cannon. The individual shots, in this case about 55 for a six-pound cannon, which could vary from .80 to 1.25 caliber, were placed in a tin cylinder with a tin top and a wooden bottom against the powder cartridge. The tin case and wooden bottom disintegrated as it exited the muzzle when fired. (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Case shot packed in sawdust in a tin cylinder that would have had a wood bottom and tin top.

Figure 4. Below are the case shots recovered at Fort Jefferson after the tin case had disintegrated and the shots were dispersed in a random scatter.

While searching for the lead musket balls, a couple of 0.9-inch iron balls were found. The search area expanded, and while some iron shots were found overlapping with the musket ball firing range, another relative position pattern was revealed for the iron case shot. This pattern was elongated, much larger, and fanned out conically (see Fig. 1). Measuring northwest from the northwest bastion’s blockhouse of Ft. Jefferson, the pattern began at 193 yards and fanned out. The farthest iron shot was found 333 yards from the blockhouse. The shot spread at 200 yards from the fort’s bastion was 56 yards wide, and at 300 yards, the spread was 85 yards wide. So far, 51 of these shots have been found 6 to 11 inches deep in the ground. Most shots are .88 to .90 calibers, with one .812 and two 105.24 calibers. Based on the weight of a solid shot from a six-pounder cannon, the weight of a case shot fired would equal to 82 oz., plus the weight of the wood bottom and tin canister. With each found shot averaging 1.46 oz. weight, approximately 55 shots were fired in each round canister. There could have been a loss of weight or caliber due to rust.10

Recovering these artifacts was difficult because of trash in the soil, the depth of the iron balls, the large search area, the vegetation, and the terrain.10 Please refer to note #11 about permission at the site and disposition of artifacts.

We believe the case shots are either remnants of a practice firing of a case shot round to determine range or a case shot fired at attacking Indians on Sept. 5th, 1792, in an attempt by Indians to get to the cattle pen north of the fort. Fort Jefferson’s Commandant David Strong wrote General Wilkinson, “There were a few pieces(cannons) discharged, and they soon disappeared.” 11

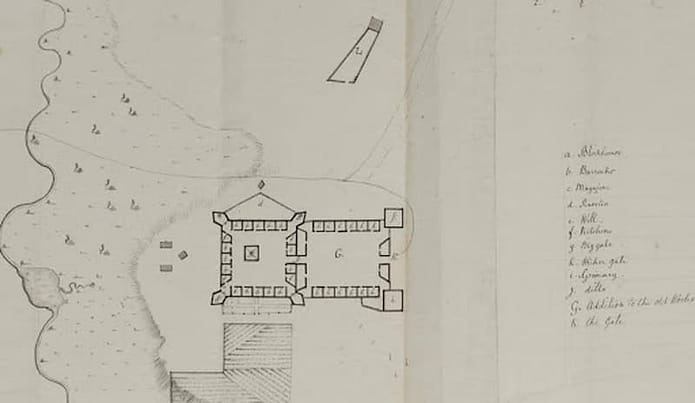

Col. Winthrop Sargent, Adjutant General to St. Clair’s army, reported the army had 10 pieces of cannon on the October 1791 campaign. Two were left for the defense of Ft. Jefferson as the campaign continued north to its disastrous defeat on Nov. 4, 179112. In a “Return of Military Ordnance and Military Stores at Ft. Jefferson,” the two pieces are listed under “Iron Ordnance” as a six-pounder (Figure 5) and a howitzer, 5½ inches (Figure 6). Case shot ammunition is listed for both cannons.13

Howitzers fired exploding shells, and six-pounder cannons did not. Six-pounder cannons fire a solid ball of 6 pounds, or a case shot or grape shot equaling the weight of six pounds. Both types of cannon fire iron case shot and grape shot (a larger version of case shot). FoFJ volunteers have found part of an exploded shell fragment, which appears to be fired from a 5 and ½ inch howitzer, south of where Ft. Jefferson was located. Because of that find, the 5 ½ howitzer was, at times, placed in one of the south-facing bastions, and the 6-pounder cannon was in the northwest blockhouse. Therefore, we conclude that the iron case shot found north was possibly fired from a six-pound cannon.

A 1792 sketch of the fort shows a cannon barrel pointing from the northwest bastion opening (Fig. #7).14 It appears the barrel protruding in the NW bastion would be a six-pounder since a howitzer’s barrel on a carriage would not be able to extend out through a firing port. Another drawing of the fort also made during the fort’s existence, shows a cannon in both of the north-facing bastions.15 This drawing of an overhead view of the fort (Fig. 8) shows the cannon in the NW bastion having a longer barrel. Because of finding the exploded shell fragment along with a three-grape shot south of the fort, the soldiers must have moved the howitzer around. This shell fragment and grapeshot south of the fort were found close to the fort wall. A howitzer had a shorter range than a six-pounder because of a shorter barrel and less powder used.

The shotgun-like spread of 50 to 75 case shots was a more effective deterrent than a regular cannonball or even an exploding shell. The iron case shot area matches the distance and spread of documented experiments with a six-pounder iron case shot from the period.16 The case shots were possibly fired in the Sept. 5, 1792, Indian attack or could have been part of a test firing to check range with a certain elevation and powder charge for practice sometime during the fort’s existence from October 1791 to 1796.

The Friends of Fort Jefferson will continue to research documents and artifacts to tell the Ft. Jefferson story of the formation of the early U.S. Army, the struggles of the new nation, and the triumphs and tragedies of the Western Confederation of Indian tribes.

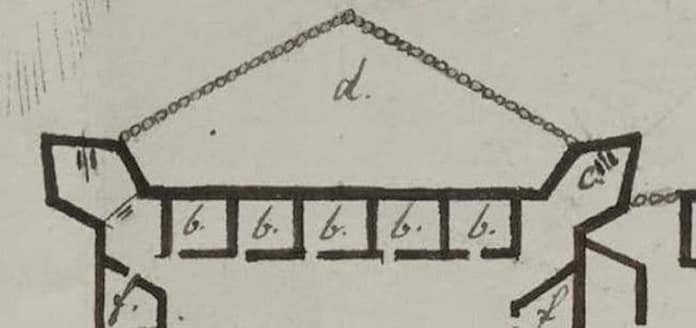

Figure 7. Below is a Fort Jefferson drawing, which was made during its existence, probably in 1794. It is a view looking from the West toward the East. (Indiana Historical Society)

Friends of Fort Jefferson want to recognize and thank Ian McAtee, who secured permission for the survey, found the site, and brought Wayne’s Legion Research Group from Ft. Loramie to add their expertise. Special thanks to Bill Light, who made a 3-D print model of the fort. We are confident he has located the perimeter of the fort location within a foot or two. He also figured out how to determine the caliber of fired musket balls and then expanded the chart for all lead ball sizes. Thanks to Paul Ackermann, former curator at the U.S.M.A. Museum at West Point, for helpful advice.

Notes:

1 See Frazer Wilson, Fort Jefferson: The Frontier Post of the Upper Miami Valley (Reprinted from a 1950 copy by Friends of Fort Jefferson in 2020 with limited copies for sale at the Garst Museum, Greenville, Ohio). For accomplishments, see Richard H. Kohn’s Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783-1802 (New York, N.Y.: The Free Press, 1975). For an overview of the Ohio-Indian War, see Alan D. Gaff, Bayonets in the Wilderness: Anthony Wayne’s Legion in the Old Northwest (Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press, 2004) or Wiley Sword, President Washington’s Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press, 1985).

2 Friends of Fort Jefferson (FoFJ) also researches and publishes information. FoFJ has 501-C3 status and writes a “Friends of Fort Jefferson” column on mycountylink.com

3 Anthony Wayne: A Name in Arms, Richard C. Knopf, ed. (Pittsburgh: U. of Pittsburgh Press, 1960) 185.

4 St, Clair’s Orderly Book (Adjutant Crawford’s Orderly Book). Detroit, Michigan. Detroit Public Library, Burton Collection, typescript copy, 55.

5 Wayne’s orders see Anthony Wayne: A Name in Arms, 65. For Wilkinson’s orders, see David A. Simmons, An Orderly Book from Fort Washington and Fort Hamilton, 1792-1793. Sub Legionary Orders, James Wilkinson, Jan. 6. 1793. www.librarycincimuseum.org

6 Daniel Sivilich, Musket Ball and Small Shot Identification (Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 28-31.

7 Frazer Wilson, Journal of Daniel Bradley, (Greenville. Oh.: Frank H. Jobes & Son, 1935.) 37, 41, 43, 44. Wilson, Fort Jefferson, 28. Wilkinson to Wayne, Sept. 12, 1792, which included the David Strong letter as an enclosure. Anthony Wayne Family Letters, Clements Library, University of Michigan. Harris to Hodgdon, July 6, 1792, and July 15, 1792, Papers of the War Department, www.rrchnm.org/papers-of-the-war-department/

8 George Smith, An Universal Military Dictionary (London: J. Millan, 1779) LAB, 156, 316.

9 David McConnell, British Smooth-Bore Artillery, A Technological Study…

(Ottawa, Canada: National Historic Parks and Sites Environment Canada – Parks) 319.

10 The detection survey was done on private property with owner’s permission. Special thanks to them. Please note that no metal detecting or digging is allowed on the Fort Jefferson state-owned property. It is illegal. All artifacts are being held for Darke County Parks in anticipation that they will receive control of the property. That is where the ownership belongs, to the people of Darke County. The Darke County Parks plan to improve the park facilities and make it an educational center if and when they obtain the property.

11 In most instances, “pieces” referred to artillery during this period. David Strong’s letter enclosed in Wilkinson to Wayne, Sept. 12, 1792. Wayne Family Papers. Clements Library, U. of Mich.

12 Winthrop Sargent, Diary of Winthrop Sargent, Adjutant General During the Campaign of 1791 (Wormsloe, Ga.: Wormsloe Press, 1851) 9, 17.

13 United States Congress, “Return of Ordnance and Military Stores at Fort Jefferson,” American State Papers, Military Affairs, 1:59.

14 Fort Jefferson, M0367, Box 1, Folder 39. Northwest Territory Collection. Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, Ind.

15 Fort Jefferson, Henry Burbeck Papers, Box 5. U.S. Military Academy Library, West Point, N.Y.

16 For experiments, descriptions, construction, and use of iron case shot, see Adrian B. Carauna, “Tin Case or Canister Shot in the 18th Century” (Access Heritage: https://www.militaryheritage.com/caseshot.htm) reproduced from Arms Collecting Vol. 28, No. 1. Also see George Smith, An Universal Military Dictionary, LAB.