In just a few weeks I will be twenty-years old—on April 15, 1943, to be exact. Unfortunately, while wisdom comes with age, sometimes it doesn’t arrive in time to prevent really dumb things, like what I almost did to my mom. I was having problems learning to fly by instruments (that’s my excuse). I was frustrated and irritated. So I decided to air out my frustrations by writing a silly letter to my mom containing a very clumsy attempt at humor. Luckily my best friend, Ted Landrum, had more sense than I did. Here’s what happened…

‟Dear Mrs. Cobb, it is with greatest sadness and regret that we inform you of the death of your son, Aviation Cadet Lewis M. Cobb, during an Instrument Flight Training session. We are convinced that Lewis would have been a first-class Naval Aviator, perhaps one of the greatest pilots ever to traipse the wild blue yonder. It is a tragedy that the world did not get to witness his great ski—”

‟You are NOT sending that to your mother, Cobb. Absolutely not!” Ted Landrum snapped.

I didn’t realize that Ted had been looking over my shoulder while I was writing the letter. ‟Come on, Landrum, it’s just a joke, okay? It will be in my handwriting—she’ll figure I could not be writing about my own death. Relax, man!”

‟Yeah, and what if she has a heart attack and dies before she can put two and two together? Gimme that, you moron.”

Before I could react, Ted reached down, grabbed the letter and tore it to bits. He cuffed the back of my head hard enough to knock me on the floor.

‟HEY! Take it easy, Dilbert! It was a JOKE!” I shouted as I picked myself up off the floor.

‟You don’t ever joke about that, you idiot! Don’t you realize your mom knows women—probably her friends—who have been getting letters like that for the past year? Letters that aren’t jokes?”

Then I remembered that Landrum’s family had received one of those letters six months ago. His brother had been a gunner on a B-17 bomber crew. His aircraft had gone down in flames over Germany—no survivors.

Chastened, I swallowed my wounded pride. ‟Oh, man, Ted—I am so sorry. I wasn’t thinking.”

‟That’s for sure,” he said, his face red with anger. A tear leaked out of the corner of his eye, then my best friend turned on his heel and stalked out of the barracks, leaving me embarrassed and ashamed. What was I thinking?

Perhaps I’d better explain: I actually did crash into a forest thinking I was landing on the airfield at Valdosta, Georgia. But I wasn’t flying an SNV when I crashed. I was flying the ‟Blue Box,” the Link Trainer, a flight simulator which was sitting in a building at Pensacola. At this point in our training we were learning how to fly by instruments—it was a lot safer to cut our teeth in the simulator before being set loose in a real airplane. The training mission I was given involved navigating blind from NAS Pensacola to the municipal field at Valdosta using instruments only—no visual references. I failed to correct for wind drift and missed the runway by about a thousand yards. My instructor thoughtfully informed me that I was wrapped around a Carolina pine tree in a forest somewhere south of the landing strip, and that emergency personnel were scraping up my remains with a stick.

**********

There’s a bit of history regarding the Link Trainer that involves my dad, at least in an oblique way. Years ago, my father, Donald K. Cobb, aka. DK, had won the contract to fly mail between Los Angeles and Mexico city. He and other very skilled private pilots were garnering the market for airmail delivery. But this did not set well with the Army Air Corp, which was flush with pilots who had nothing to do once World War 1 ended. The Army brass pulled some strings to capture the airmail contracts for the AAC, taking them away from the private pilots. My dad was part of the ‘collateral damage’ of the political machinations, losing his airmail route to an Army Air Corp pilot.

There was only one problem: the Air Corp pilots did not possess the training or the many hours of flight experience the private pilots had, especially with respect to flying in bad weather. Within seventy-eight days of winning the contracts, there were twelve fatal crashes of AAC pilots, most due to flying in instrument conditions. It became clear that a reliable, safe means of training pilots to fly in instrument flight conditions was necessary.

Enter Edwin Link. Back in the 1930s he developed and patented a flight simulator that was perfect for training pilots to fly in instrument conditions. It looked like a carnival ride contraption, a small, brightly-painted, blue imitation fuselage, complete with stubby yellow wings, tail, and a cockpit outfitted with a control column, rudder pedals, and instrument panel containing a full set of flight instruments. The crazy thing could move on all three axes—pitch, roll, and yaw. For the ‘pilot’ sitting in the cockpit, it felt like you were actually flying. The ‘Blue Box,’ as it became known, was initially purchased by many carnivals for use as a carnival ride. That fact probably did not help the AAC brass’s opinion of the Link Trainer—they did not regard it as a serious pilot-training device.

Until 1934. Link had finally convinced the AAC honchos to sit for a demonstration of the contraption. On the day the meeting was to be held, the airport was socked in with fog. The brass was certain the meeting would have to be rescheduled because Link was flying to the meeting, and everyone knew that flying and landing safely in such conditions was impossible. Everyone, that is, except Edwin Link, who landed perfectly on the foggy day and was able to keep his appointment with the AAC officers. That was all it took: in May of 1934 the Army Air Corp ordered six Link Trainers. By the time Ted Landrum and I entered the Naval Reserve pilot training program, thousands of Link Trainers were in use by all branches of the military.

**********

‟How did you get number 5 again, Wright? This is the third hop in a row you’ve had that Blue Box.” I was irritated, because I wanted number 5.

‟Just lucky, I guess,” Bob Wright said with a grin

‟Bull! You’re hustling someone.”

Wright winked, but didn’t respond as he climbed into the cockpit of Link Trainer number 5.

Bob Wright was known as the squadron hustler. Whenever we were given passes to get off the base, Wright always managed to cop a vehicle from the base motorpool, even though cadets didn’t have that privilege. When it came to games, whether it was blackjack, poker, or Acey Deucey, Bob always had an angle. He had this deceptive way of looking innocent and naive, pretending he didn’t know much about the game. If you took the bait and got suckered into a game with him, he would soon separate you from your money. It didn’t take long for the news to get around the squadron that Wright was a hustler, and if you entered into any sort of match with him you might as well kiss your cash goodbye. After a while, nobody wanted to play with him if money was involved. Some of us suspected he was dealing from the bottom of the deck, but no one had ever seen him do it. I think he was just really good at the games.

Not sure who he was hustling, but whoever it was always got Bob on the schedule for number 5. The big deal with Link Trainer number 5 was the WAVE who ran that particular simulator (many, perhaps most, of the simulator controllers were WAVEs). She was one gorgeous woman, with a swell personality to boot. Everyone in my cadre had dreams of marrying that gal. All my buddies agreed that Miss Cranfeld would be quite a catch. That was until we saw her boyfriend dropping her off at the base training center several weeks later. He was really built. Landrum said that he was the intramural boxing champion on the marine side of the base. Not someone I’d want to tangle with, so I sadly abandoned my romantic thoughts about the WAVE on Trainer number 5.

My plotting board under my arm, I climbed into number 7. As I situated myself in the cockpit and pulled the hood down, I decided that it was a good thing Bob Wright had number 5 and not me; I didn’t need the distraction of a lovely lady. Instrument flight training was not going well for me, and I needed to concentrate.

**********

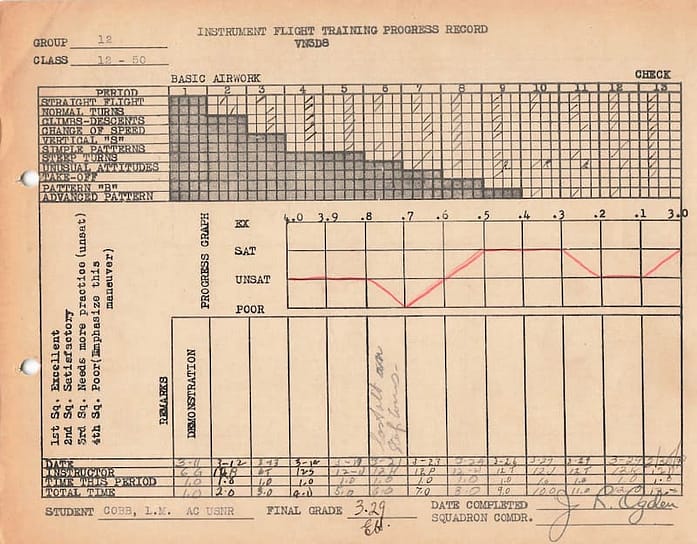

There were twelve ‘periods’ of instrument flight training, each gradually increasing in difficulty. I was at period six, and all the evaluation grades of my instrument flights to date were ‘unsatisfactory.’ I had just completed period six—steep turns—and had received the lowest mark of my training experience: ‘poor.’ The instructor added a notation: lost altitude on steep turns. The fear of washing out of the aviation cadet program was on me once again. I started grabbing extra simulator hours, hoping to get the hang of instrument flight before the Navy decided that I’d never make it as a pilot.

On March 23rd, I strapped into an SNJ-4 Texan, with Ensign Winecoff in the seat behind me. It counted as a solo flight because at this point in our training, the passenger was not coming along as an instructor, but as a safety feature. I’d be flying with the hood down, so the passenger was along to keep me from crashing the airplane if I did something stupid. It was another bad flight. I was marked down as unsatisfactory in steep turns, the vertical ‘S’, change of speed, and climbs and descents.

I taxied to the flight line and went through the brief shut-down procedure as Winecoff disembarked from the aircraft. When I hopped down onto the apron he showed me the evaluation marks. They weren’t good.

‟Come with me, Cadet.”

He turned on his heel and walked stiffly into the hanger where the small ready room was.

‟Pour us both a cup of coffee and sit down.”

After I sat down, he glared at me and demanded, ‟Tell me what you’re doing wrong.”

‟I don’t know, si—”

‟Yes, you do,” he snapped, interrupting me. ‟Tell me what you’re doing wrong!”

I stalled because I didn’t want to parrot the obvious answer that was drilled into us day after day in all of our classroom time. I frankly didn’t believe it.

He just waited, eyebrows raised.

I stared down at my coffee cup and finally admitted, ‟I don’t believe what my instruments are telling me. I believe what my body is telling me regarding the attitude of the aircraft. I’m fearing that the instruments are wrong—maybe they’re not calibrated, maybe they’re defective. When I was flying under visual conditions, my senses were telling me very accurately what the aircraft was doing, so now I’m trusting them when I fly under the hood.”

‟Your senses are not accurate, whether you’re flying in visual or instrument conditions—they lie to you in both cases. You cannot trust them.”

‟With all due respect, sir, I disagree. I did fine following what my perceptions were telling me when I learned under visual flight conditions. I trusted my senses.”

‟And that’s your problem, Cobb. Your senses are not any more accurate under visual conditions than they are in instrument flight.”

‟But—”

‟No, listen to me. The difference is that when you are flying in visual conditions, your eyes are constantly correcting your lying senses—you’re just not aware that’s happening. What you see overpowers your sense of balance and everything else. You can see the horizon and so you know whether you are banking, or whether your nose is pitched down or up, even though the impressions from your other senses might conflict with what you see. It’s just that the voice of your sight is louder than the voice of your balance and your other senses.”

That stopped me. I hadn’t thought of that. It had not occurred to me that the corrective of sight overpowered my other sensations in visual flight. Winecoff was saying that sight was my trump card over all my other perceptions—it overruled whatever message they were sending.

He looked at his watch. ‟I gotta go. Tomorrow you and I are going up again, and I want you to do something different. Tomorrow, I want you to trust your eyes, but only as they are focused on your instruments. Watch your instruments, trust them, and believe what you are seeing on your instruments. Don’t believe what your other bodily senses are telling you. If you’ll do this, it’s almost like flying in visual conditions—even under the hood. It’s visual inside the cockpit. It’s just that you are seeing and believing your instruments in the cockpit, rather than the horizon which you can’t see. Let your sight of your instruments correct what your other senses are trying to tell you.”

After he left, I sat for a long time mulling over what Winecoff had said. I hadn’t thought of the conflict between what I can see and what I can feel. I’d never considered that the former constantly corrects the latter, but it began to make sense. Since I could not see the horizon, I needed to fix my eyes on what I could see—my instruments—and have faith that they were correct, even if my feelings were saying something different.

The next day’s flight wasn’t perfect, but for the first time my marks were all satisfactory. My flying began to improve steadily. On March 30, 1943, I successfully completed instrument training and graduated into the next phase.

**********

The door to the barracks flew open, and a lieutenant entered and barked, ‟Attention!”

This was not a good time for an inspection; it was downtime for the squadron and we were relaxing in various disheveled states of dress. I leapt off my bunk in my skivvies and stood at attention wondering what the devil was going on. Bob Wright whipped the blanket on his bunk over the evidence of a poker game involving real money and stood ramrod straight with that innocent, poker-faced expression he’d perfected. The other players concealed their cards in their hands as they snapped to attention.

Lieutenant Commander Ogden, our squadron commander, stepped in. He looked around the barracks until his eyes locked on Rocky Aldridge. ‟You’re done. Pack your kit and report to Squadron HQ. Bring your duffle with you.” Ogden turned on his heel with the lieutenant in tow behind him.

We all looked at Aldridge. ‟What was that all about?”

He hung his head and walked over to his bunk and began packing his duffle.

‟C’mon, Rocky, what’s going on?” Landrum pressed. ‟Surely you haven’t flunked out.”

‟No, but I screwed up. I thought I could get away with it, but…”

‟What did you do?” I asked.

‟Buzzed one of the local ranches. I didn’t think I’d be caught. I didn’t see anyone who might report my tail number. Guess I was wrong about that—someone must have seen me.”

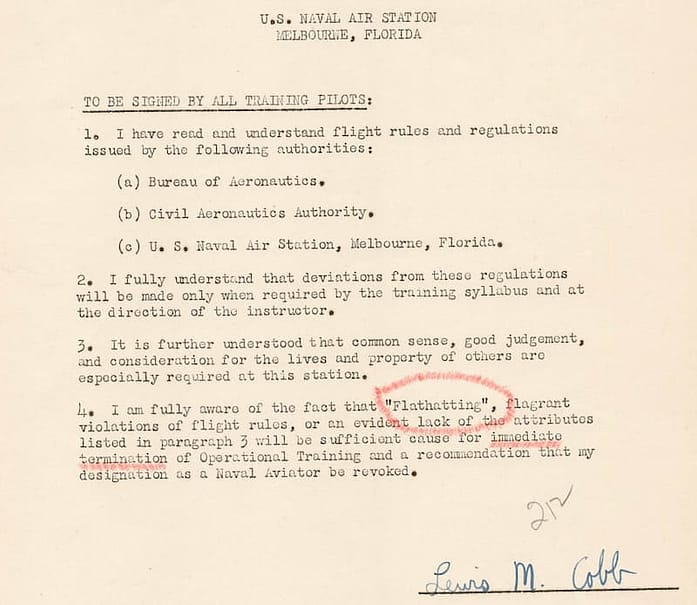

‟You were flat-hatting?” Landrum asked incredulously.

Aldridge nodded glumly as he continued to pack his things.

‟You moron! You signed a statement about flat-hatting when you arrived here. You knew the rules. You knew what would happen,” Ted said, raising his voice. Landrum, you might have noticed, had a hair trigger on his anger. Otherwise, he was a pretty swell guy.

‟No, no, this cannot be. We cannot allow this,” I said, grabbing Landrum’s arm. ‟Come with me, Ted. We’ve got to change their mind. This is stupid—Rocky’s the best pilot in the squadron.”

While Rocky was still packing his kit, I dragged Ted over to Squadron HQ, ignoring Landrum’s protests. A WAVE serving as the squadron clerk was sitting at the desk.

‟Yes?” she said, looking up from a stack of papers.

Landrum raised his eyebrows and looked at me as if to say, this is your play, crazy man.

‟Ma’am, I’ve got an emergency—I mean, we’ve got an emergency. I need to see Commander Ogden.” When I said ‘we’ Ted rolled his eyes and shook his head.

‟And what sort of emergency would that be, Cadet?”

‟Oh, um, it’s—it’s, ah, classified.”

‟Classified,” she repeated, narrowing her eyes. At that moment I happened to notice she had a very pretty pair of eyes. I also noticed she didn’t really believe me.

‟Yes, ma’am. It’s rather urgent,” I insisted.

Landrum shot me a look that said, what are you dragging me into, Dilbert?

A minute later we were standing at attention before our squadron commander. His aide, the same lieutenant that had barged into the barracks, was standing beside the commander’s desk.

‟At ease, Cadets. So what is this classified emergency you wish to report? This had better be good.”

I swallowed and then managed to say, ‟Sir, with all due respect, you can’t wash Cadet Aldridge out of the program because of one foolish mistake. The Navy needs pilots like him. He is the best pilot in our cohort.”

‟Yes, well, we’re about to find out how good he is with a mop or chipping paint. Now, what’s your ‘classified emergency,’ Cadet?”

‟I’m sorry about that, sir, I needed something to get me into your office. The only emergency is that we are about to lose the finest pilot in our cadre. I know he violated regulations, sir, but can’t you make an exception? Maybe give him some other form of punishment or something?”

‟Listen, Cobb, I reviewed his training record as soon as that angry rancher left my office. I am well aware that Cadet Aldridge is a good pilot. But my hands are tied—I have to follow orders just like you do. The standing order is that when a flat-hatting report is filed, the offending pilot is drummed out. I don’t have a lot of discretionary leeway in this case.”

I thought for a moment. ‟Sir, you said that when a report is filed you have to act.”

‟Correct. I have no choice.”

I nodded. ‟But what if the citizen’s complaint is withdrawn, so the report is sort of, ah, not filed.”

‟That’s not likely. That rancher lost seventy feet of fence, his cattle were scattered, and two of them are still unaccounted for. He was furious. I thought he was going to jump over the desk and punch me in the nose. I don’t think he’s going to back down.”

‟But, sir, what if he did withdraw his complaint?”

‟Yes, I suppose at that point I would have the discretion to decide how to punish the offender.”

‟So, what if Cadet Aldridge volunteered to spend, say, twenty hours a week working for the rancher—at no charge—repairing the fence, shoveling the barn, doing whatever the rancher needed. And what if Cadet Landrum and I also volunteered? Might it be possible to convince him to withdraw the complaint in return for free labor?”

At this moment, Landrum glanced at me with an are you serious? expression. Ted was getting pretty good at communicating without opening his mouth.

Commander Ogden stared at me for a long moment, scratching his chin. Finally he asked, ‟Would anyone else in the squadron also volunteer to save Aldridge’s hide?”

‟Yes, sir, two or three more, at least.”

‟I see. Perhaps I can give the matter some consideration.”

Ogden’s aide spoke up, ‟Sir, can you really do that? Might it cause these young hotshots to think there are no teeth in the regulations they sign.”

The commander turned to his aide. ‟Yes, there is that danger, lieutenant. But on the other hand, what we are seeing here, lieutenant, is probably worth the risk. It’s unit cohesion—something we always strive to create. We want them to feel responsible for each other.

‟If Cadet Aldridge is capable of creating such loyalty around him, it’s a sign he’ll be a really good officer, regardless of how well he flies.”

Commander Ogden looked at Ted and me and waved his hand. ‟Dismissed.”

As we left his office we heard him say to his aide, ‟Get me a vehicle from the motorpool. I’m going to call on that rancher.”

**********

Commander Ogden arranged a deal with Clarence Mitchell, the rancher. They agreed that Rocky, Ted, and I would work twelve-hour days, Saturday and Sunday, for three successive weeks. If we did that, he would withdraw the complaint. In the meantime we had to keep to our regular training schedule Monday through Friday.

Even though the deal specified that Aldridge, Landrum, and I would show up for work, when the deuce-and-a-half pulled up to the barracks on the first Saturday, the whole squadron piled in.

In addition to shoveling manure out of the barn and repairing the broken fence and making other repairs and improvements the ranch required, we also fenced an additional thirty acres that old Mr. Mitchell had wanted to do, but never had the time or energy for. For the first day, Mitchell was a little cold and harsh to us, but by the third Saturday he was like a dad-away-from-home to the whole squadron. On our last Sunday working for him, he put on a delicious steak-fry for the whole squadron, including Commander Ogden and all the support personnel.

As we were piling into the truck for the ride back to the base, Commander Ogden waved Rocky and me over. ‟Well done, Cobb,” he said to me.

Turning to Rocky, he said, ‟Aldridge, one more screw up and you are out. You have a great gift of leadership; use it, but you must use it wisely for the good of those around you.”

[Author’s note: This particular flat-hatting episode was invented, though NAS Pensacola did have an occasional problem with it. However, the instincts of Lewis Cobb to protect and defend those he flew with, illustrated in this story, were demonstrated many times during the war. Cobb received multiple awards and citations for bravery in combat, including circling over downed pilots until they were rescued, at great danger to himself.]